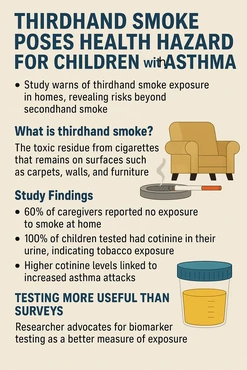

A study says its a health risk for children with asthma

May 23, 2025

-

Thirdhand smoke lingers in homes and may expose children to toxic substances even without active smoking.

-

Biomarker testing revealed tobacco exposure in all children studied, despite 60% of caregivers denying exposure.

-

Asthmatic children showed higher cotinine levels and increased asthma attacks, emphasizing the need for more accurate exposure assessments.

You may be familiar with the concept of secondhand smoke breathing in the smoke from someone elses cigarette. But what about thirdhand smoke? Its a thing, and a new study from Tulane University warns that its a health hazard, especially for children who have asthma.

The study, published in the Journal of Clinical and Translational Science, reveals that while most parents report no tobacco smoke exposure in their households, biomarker testing tells a different story.

Researchers surveyed caregivers of 162 children living in federally subsidized public housing in New Orleans, Cincinnati, and Boston. While 60% of the respondents believed their children were not exposed to environmental tobacco smoke (ETS), urine analysis showed that 100% of the children had measurable levels of cotinine, a nicotine byproduct and reliable marker of tobacco exposure. Over 90% of the children showed intermediate levels, indicating consistent exposure.

These findings do not imply that the parents are lying but rather speak to the invasive nature of thirdhand smoke and how difficult it is to remove, said Katherine McKeon the studys lead author.

What is thirdhand smoke?

Thirdhand smoke refers to the toxic residue that remains on carpets, walls, furniture, and other surfaces long after a cigarette has been extinguished. Children can be exposed by touching contaminated objects or inhaling resuspended particles while playing. Unlike secondhand smoke, which is directly inhaled, researchers say thirdhand smoke lingers for months and becomes increasingly toxic over time, evading standard cleaning methods.

The researchers emphasize the insidiousness of this exposure, particularly for children with asthma. The study found a strong link between elevated cotinine levels and increased asthma attacks. However, there was no such link between reported ETS exposure by caregivers and asthma flare-ups, highlighting a concerning gap in perception versus reality.

McKeon advocates for broader use of biomarker testing like cotinine analysis, calling it a more accurate and objective measure.

Our research confirms that relying on caregiver surveys to assess childrens tobacco smoke exposure is inadequate, McKeon said. This misclassification may hinder proper asthma management and delay critical interventions.

#home #thirdhand #cigarette #smoke